Fallopia, Japanese knotweed: planting, growing, and care

Contents

Fallopia in a nutshell

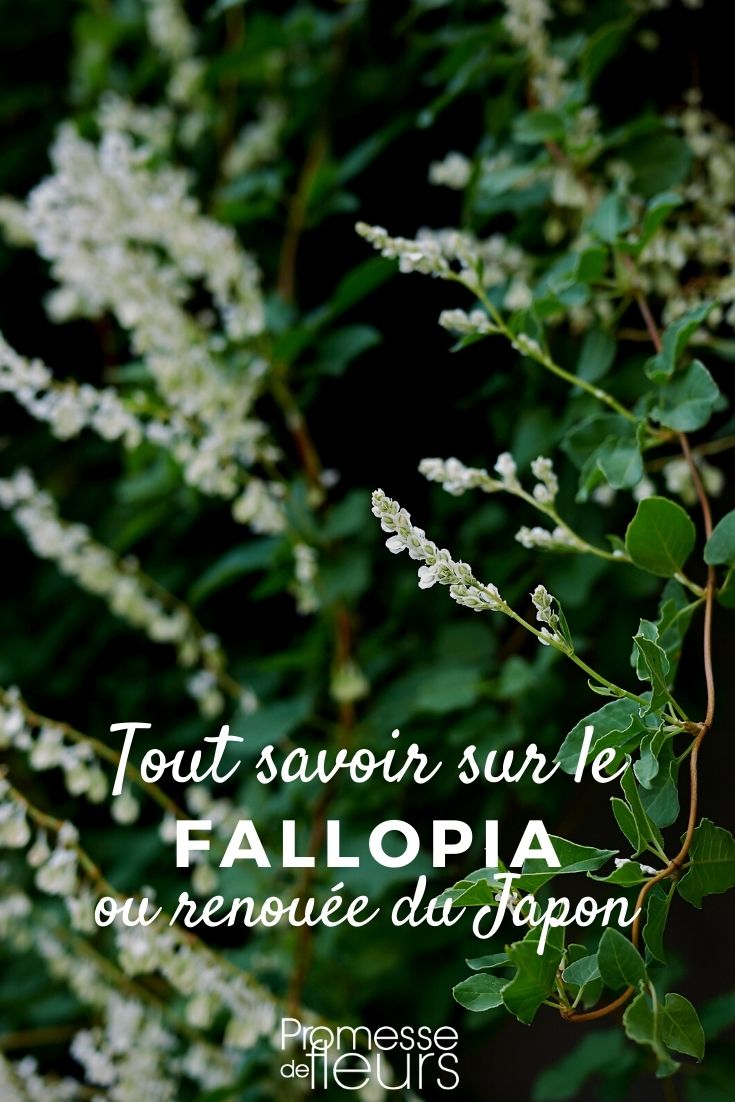

- Knotweeds (Fallopia) are very vigorous shrubby or climbing plants

- With rapid growth, they offer green foliage or highly decorative variegations

- Their delicate white summer and autumn flowering is nectariferous and attracts pollinators

- They adapt to all types of soil and all exposures

- Hardy, they are free from diseases and pests

- It is difficult to control their invasive character

The word from our expert

The Knotweed includes various species of annuals, perennials, or shrubs with decorative foliage and flowering. Formerly called Polygonum and then Reynoutria, it is now named Fallopia by botanists. Among the most common species, Fallopia japonica (Japanese Knotweed) is the best known, but others have been cultivated, such as Fallopia aubertii, F. sachalinensis, or F. bohemica. Their exuberant growth and exceptional vigour make them difficult to control, especially when conditions are favourable. In moist soil, it can spread unchecked, and the climbing species can reach up to 12 metres, enabling them to quickly cover unsightly vertical elements or conceal an unattractive fence. With green foliage or bright variegations, its summer and autumn flowering, in shades of white tinged with green or pink, is highly attractive to insects, which find an abundance of nectar there. Free from diseases and never attacked by pests, it is a hardy plant that is very easy to grow. However, it should be used with consideration for its tendency to spread.

Description and Botany

Botanical data

- Latin name Fallopia (formerly Polygonum and Reynoutria)

- Family Polygonaceae

- Common name Japanese knotweed, Japanese fleeceflower

- Flowering summer and autumn

- Height 2 to 12 metres

- Sun exposure sun, partial shade, shade

- Soil type any moist soil

- Hardiness down to -30°C

The Fallopia is a plant with a tumultuous history. Belonging to the Polygonaceae family (which includes, for example, Buckwheat, Sorrel, Rhubarb, and Persicaria), and native to the southern and oceanic regions of East Asia, it is indeed a genus whose name has changed three times. Its stems with prominent nodes first earned it the name Polygonum (from the Greek ‘poly’, meaning ‘many’, and ‘gonu’ for ‘knees’). Its vernacular name, Knotweed, also means ‘many times knotted’. Later, it was classified by the Guinochet flora (1973) in the genus Reynoutria, before finally becoming Fallopia, in homage to Gabriele Falloppio, an Italian naturalist of the 16th century.

This genus includes climbing annuals (Fallopia convolvulus, F. dentatoalata, F. dumetorum), more or less shrubby perennials (F. forbesii, F. japonica, F. sachalinensis), climbing perennials (F. baldschuanica, F. cynanchoides, F. denticulata, F. multiflora, F. scandens), semi-climbing perennials (F. cilinodis), and climbing undershrubs (F. aubertii). Cross-breeding has also given rise to hybrids such as Fallopia x. bohemica (from F. japonica x F. sachalinensis).

Originally, Fallopia japonica grew naturally in the humid undergrowth of China, Korea, Japan, and Siberia.

In the early 19th century, Philipp Von Siebold, a physician and botanist stationed in Japan, brought this plant back to his garden in the Netherlands. Due to its very elegant habit, beautiful autumn flowering, and nectar-rich blooms, it quickly became highly sought after in both Europe and the United States. It was even awarded a gold medal by the Agricultural and Horticultural Society of Utrecht (Netherlands) in 1847 and was described as “the most interesting plant of the year,” valued as a forage plant, melliferous plant, and soil stabiliser. Thus, Fallopia japonica, like Fallopia sachalinensis, which gradually naturalised on both continents, began their colonisation process, spreading to the point where they are now considered by the Nature Conservancy, particularly concerning Fallopia japonica, as among the 100 most problematic exotic species. The Species Survival Commission of the International Union for Conservation of Nature also regards it as one of the “world’s worst invasive alien species.”

Fallopia sachalinensis

Today, it is widespread across our territory, with higher concentrations noted in the northwest, southwest, and east. Its expansion dynamics are such that it sometimes displaces native species. Its management and eradication in wild spaces have become problematic.

With very rapid growth, some species are evergreen, while the most commonly used ones are deciduous. Their foliage dries and disappears in winter, only to regrow vigorously from the stump the following spring. Depending on the species, the hollow stems are erect, voluble, or creeping. They are sometimes tinged with red, particularly in early growth. The leaves are alternate, single, and entire, triangular, cordate, or more or less ovate and sagittate, borne on petioles whose insertion at the stem is surrounded by a thin, brown, cylindrical membranous sheath called an ochrea, a typical organ of the Polygonaceae family. They measure from 2 to 30 cm long and up to 25 cm wide, depending on the species. Generally matte green, the leaves can also display very beautiful variegations in light green, white, and creamy pink (Fallopia bohemica ‘Spectabilis’ or Fallopia japonica ‘Variegata’) or be entirely golden (Fallopia aubertii ‘Summer Sunshine’). It should be noted that these species with more colourful foliage are generally less invasive.

The beautiful foliage of Fallopia japonica ‘Variegata’ and Fallopia aubertii ‘Summer Sunshine’

The shrubby species typically reach 2 to 3 metres in height, but those with a climbing or creeping habit can extend their stems up to 12 metres, requiring both space and suitable support.

Flowering occurs between summer and autumn. The very small but numerous flowers are grouped in axillary or terminal spikes, with a more or less loose habit, 3 to 15 cm long. White with greenish or pinkish hues, they consist of 5 tepals and 6 to 8 stamens with white anthers. Nectariferous and sometimes fragrant, they attract many pollinators. The black seeds are achenes (i.e., dry fruits containing the true seed, like sunflower seeds, for example), trigonous (three-angled), enclosed in the calyx. Knotweeds spread mainly through their powerful rhizomes, capable of extending several metres, and their roots also plunge very deeply into the soil. This vigour makes managing this plant difficult, as it is rare to remove all the roots, and even a single piece left behind can give rise to a new plant. Japanese knotweed thrives in moist, deep, and fairly rich soils but can tolerate poorer and drier soils. It is commonly found at woodland edges, near watercourses, and along roadsides. Ferruginous, volcanic, and metal-rich soils suit it well, which has led to its occasional use as a phytoremediator. It can be grown in any exposure, with a preference for sun or partial shade, and tolerates drought well once established.

Very hardy, it can withstand temperatures as low as -30°C and is unaffected by diseases or pests.

The climbing species and varieties can quickly and aesthetically conceal unsightly elements in the garden, whether a facade or a fence, for example. Installing a rhizome barrier is advisable if you choose to plant this species at home, to limit its spread as much as possible.

The flowering of Fallopia baldschuanica

Different varieties

Fallopia bohemica 'Spectabilis'

- Flowering time October, November

- Height at maturity 2 m

Fallopia japonica Variegata

- Flowering time July to October

- Height at maturity 1,20 m

Fallopia sachalinensis

- Flowering time October to December

- Height at maturity 2,50 m

Fallopia aubertii

- Flowering time September to November

- Height at maturity 8 m

Fallopia aubertii Summer Sunshine

- Flowering time September to November

- Height at maturity 7 m

Discover other Climbers A to Z

View all →Available in 0 sizes

Available in 0 sizes

Available in 0 sizes

Available in 0 sizes

Available in 0 sizes

Available in 0 sizes

Available in 0 sizes

Available in 0 sizes

Available in 0 sizes

Available in 0 sizes

Planting

Where to Plant?

- Fallopia species are not very demanding regarding soil type, though they prefer light and deep soils. In moist and damp soil, their invasive character becomes more pronounced. They also thrive in sunny or partially shaded spots but can grow in shadier areas too.

- Their size and tendency to spread require careful attention, as they can quickly overwhelm and outcompete more delicate neighbouring plants. Climbing varieties need a support structure that matches their growth, meaning it should be large and sturdy enough.

When to Plant?

Planting for most perennials is best done in autumn, though spring planting is also possible.

How to Plant?

First and foremost, determine the space you are willing to allocate to your Fallopia.

- Install a root barrier around the perimeter of the designated area, to a depth of about 70 cm, leaving the top 4 or 5 cm of the barrier protruding above the soil.

- Soak the root ball in water to saturate the substrate.

- Dig a hole in the centre of your area, slightly larger than the size of the root ball, and loosen the bottom.

- Remove your plant from its pot and place it in the centre.

- Water and mulch with your chosen material.

For climbing species, position your plant near the support it will grow on.

Always install a root barrier when planting Fallopia

Maintenance

- Maintaining Knotweed mainly involves controlling its vigour.

- For climbing species, don’t hesitate to prune the stems that escape the boundaries you’ve set.

- At the end of winter, cut the dry stems at the base.

- As a precaution, and to avoid the risk of uncontrolled spread, do not place the cut stems on the compost, but dispose of them with waste intended for incineration.

Multiply

Propagation is mainly done by taking offsets and roots.

In autumn or spring, it is indeed sufficient to retrieve a piece of rootstock a few centimetres long and replant it in the desired location, then water to obtain a new young plant.

Associate

Knotweed is not always an easy plant to pair, as its vigorous growth leaves little room for less robust neighbours. Its tall, numerous stems, along with the size of its flowers, also create shade that can deprive other plants of the light they need.

However, when grown under certain conditions (in a pot, for example, or surrounded by a root barrier), you can pair it with other plants, choosing those that are vigorous enough to assert their presence. Trees and bushes will thus have a better chance of thriving. For spring, Judas Tree, Japanese Quince, Hawthorn, Forsythia, or Photinia brighten the start of the season as the young shoots of Knotweed develop. To complement their airy flowering, consider Abelia, Buddleia, Eleagnus (whose flowers are subtle but highly fragrant!), Crape Myrtle, or even Sorbaria. For perennials, Knotweed can create a contrast in the shape of the inflorescences (upright spikes) as well as in the hues (pink, red…).

For climbing varieties, an Aristolochia, a Wisteria, a large clematis like Clematis montana ‘Freda’ or Clematis rehderiana, a Hop (some of which have stunning variegated or golden foliage), an Ivy (where green is just one shade among the many available for this easy climber), a Pileostegia (its creamy-white flowering coincides with that of Knotweed), or an Ornamental Vine with fiery autumn hues can keep them company. To dress their base, use ornamental grasses (Miscanthus, Panicum, Pennisetum), and floriferous perennials like Geranium, Aster, Japanese Anemones, or tall Bellflowers. If the exposure allows, a few clumps of ferns add beautiful texture, with their finely cut fronds contrasting with the large, entire leaves of Knotweed. The green screen provided by climbing Knotweed forms a backdrop against which the flowering of roses stands out beautifully.

With a variety like Fallopia ‘Summer Sunshine’, with golden foliage, use plants with dark foliage such as Physocarpus ‘Little Devil’, a Heuchera ‘Black Pearl’, a Chervil ‘Ravenswing’ with fern-like purple foliage and delicate white flowers, a Knotweed ‘Red Dragon’, a Cimicifuga ‘Brunette’, a Thalictrum ‘Ghent Ebony’, or a Phormium ‘Purpureum’ (in mild regions).

With the golden foliage of Fallopia aubertii Summer Sunshine, a strong contrast: Physocarpus ‘Diablo’, Chervil ‘Ravenswing’, and Knotweed ‘Red Dragon’

Did you know?

- Knotweed is an edible plant, to be consumed in moderation

The young shoots of many species can be eaten, either raw or cooked like asparagus or rhubarb, and even in pies, after peeling off the outer layer, which is more fibrous. However, Fallopia tends to grow in soils rich in metals, which are then consumed along with the plant. It is therefore better to be sure of the location where it is harvested.

On the other hand, this perennial is rich in oxalic acid, a compound also present in the human body and in many other foods, including rhubarb, spinach, sorrel, chocolate, and numerous fruits, to name just a few. Ingesting it in small quantities is not a problem, especially if you are in good health. Excessive consumption over a long period, however, should be avoided by people with joint problems or bladder or kidney stones, as it may exacerbate these conditions. Oxalic acid also has the ability to bind certain minerals, which are then excreted from the body in larger quantities, potentially leading to deficiencies.

- The most widespread vegetative reproduction in the world…

Several studies have been conducted worldwide, particularly in Europe and the Americas, and their findings are astonishing! Indeed, except in Japan, the plant appears to reproduce only vegetatively, through its underground rootstocks, and all Japanese knotweed outside its native country would therefore be one and the same plant that, by accident or through the purchase or exchange of plants, has multiplied endlessly through cloning with identical origins. This would make it the most widespread propagation by cuttings of roots on the planet…

To go further

- Our different varieties of Fallopia.

- Discover also the Persicarias, more well-behaved and highly decorative Knotweeds!

- Subscribe!

- Contents

Comments