Determining the texture of your soil: clayey, sandy, loamy

Simple tests to know your soil

Contents

The right plant in the right place, in a soil that suits it, is the main condition for a successful garden. That’s why, whether in gardening books or in our plant sheets, you will always find an indication regarding the ideal soil texture for each plant. However, not everyone has studied “pedology” * as a second language! The concept of soil texture and terms like “clay-loam” or “sandy” may seem a bit vague.

What are the different types of soils and their characteristics? How can you simply determine the texture of your soil? Here are some elements that will help you better understand your soil.

* the science that studies the formation or evolution of soil

The different types of soils and their characteristics

In terms of the pure texture of soil, there are mainly 3 essential components: sand, silt, and clay. This is known as the mineral fraction of the soil. It results from the degradation of the parent rock, located beneath the soil. These components differ based on their particle size:

- sand consists of particles larger than 0.05 mm (50µm),

- silt ranges between 2µm and 50µm,

- clay has a size smaller than 2µm.

It is worth noting that soils are rarely purely clayey, sandy, or silty: it is often a skilful mixture of these three constituents.

Sandy Soil

A sandy soil contains at least 60% sand, sometimes more. It has virtually no structure: a handful of soil crumbles too easily. It is very easy to work with and warms up quickly in spring, which is favourable for early crops. However, sandy soil is quite low in fertility as it does not retain water or nutrients.

Silty Soil

A silty soil is rich in silt. It is a soil on which, thousands of years ago, alluvium was deposited, meaning debris transported by running water. All silty soils contain at least 10% clay. It is a brown soil that feels quite soft to the touch, light, and easy to work with. It is rich, fertile, very permeable to water and air, and warms up quickly in spring. This soil is quite fragile and becomes depleted over the years. Therefore, it will need to be “fed” regularly.

Clay Soil

Clay soil sticks when wet and cracks when dry. This soil is difficult to work with and warms up slowly in spring. This type of soil is very fertile and retains water and essential minerals for plants. However, this soil is often very compact, which hinders both rooting and the exchange of gases and nutrients.

Various soils: sandy, clay-silty, and clayey

Various soils: sandy, clay-silty, and clayey

Special Case: Humus-bearing Soil

This is probably the best soil and the one found beneath our feet in forests. In reality, we are only talking about the top layer of the soil. Therefore, you can very well have humus-bearing soil from, for example, clayey soil. Naturally rich in humus, it is very fertile, particularly regarding nitrogen and nutrients. It retains water well, without excess, but is never sticky. It is very easy to work with and has a slight acidity.

And what about soil acidity?

There is also much talk about acidic soils and, conversely, alkaline soils. This also contributes to determining the nature of your soil. To learn more, visit our advice sheet “Acidic soil, neutral soil, or calcareous soil: how to tell?“

Read also

What is soil pH?Knowing Your Soil Texture: Simple Tests

Here are some very basic tests that will quickly give you an idea of your soil composition.

The sausage or ball test

Take a ball of soil and try to shape it into a sausage between your fingers.

- If you cannot do this, the soil is likely sandy.

- If you can create a nice firm sausage, your soil is likely clayey.

- If the result is somewhere in between, your soil is likely loamy.

The soil ball test is quite similar:

Make a ball of soil and throw it forcefully onto a flat surface.

- If the ball remains intact, it is highly clayey soil.

- If it completely flattens, it is highly sandy soil.

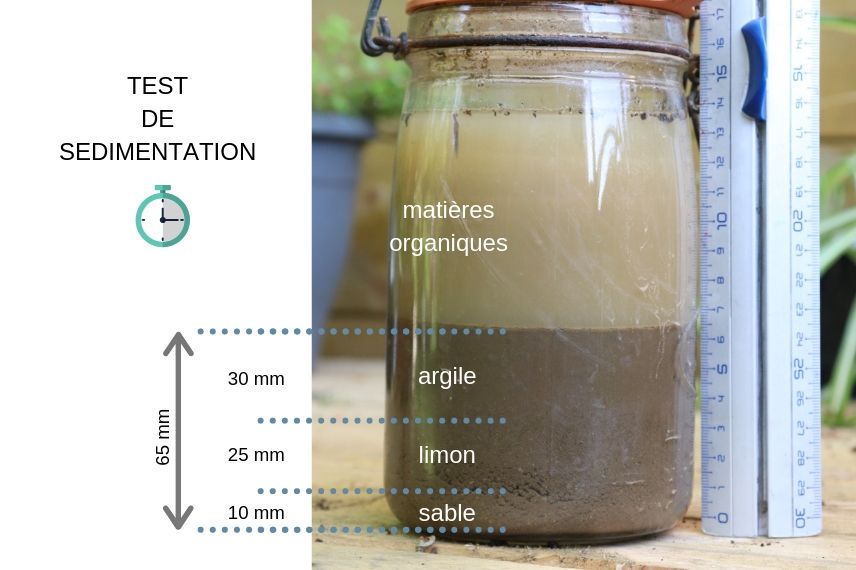

The sedimentation test

Known among agronomists as “the jam jar test“, this very simple test is nonetheless highly effective for determining the levels of sand, silt, and clay.

To carry out this test:

- Take a glass jar of at least one litre, taller than it is wide, and that can be sealed with a lid.

- Fill half the jar with soil from your garden, taken from a depth of 10 cm.

- Top up with water, leaving a few centimetres of air.

- Seal the jar and shake vigorously for 3 minutes.

- Let it sit for 30 minutes.

- Shake again for 3 minutes.

- Let it rest for at least 24 hours: the sand, being heavier, will settle at the bottom of the jar, the silt will be in the middle, and the clay will be on top. The floating particles are organic matter, forming a sort of brownish and unappetising cocktail. If your water is still cloudy after 24 hours, wait a bit longer. Decantation can take several days.

Result of a sedimentation test[/caption>

Handle the jar carefully to avoid mixing the layers again. The challenge will be to identify the different layers. Do your best! The sands are visible to the naked eye. Once you can no longer distinguish them, you are in the silt. The clay is compact and may have a slightly different colour. Once you have approximately measured the height of the different layers, you will need to convert these measurements into percentages using the following formula:

(height of a layer x 100)/total height = %

In our example, we obtain: 15% sand, 39% silt, and 46% clay.

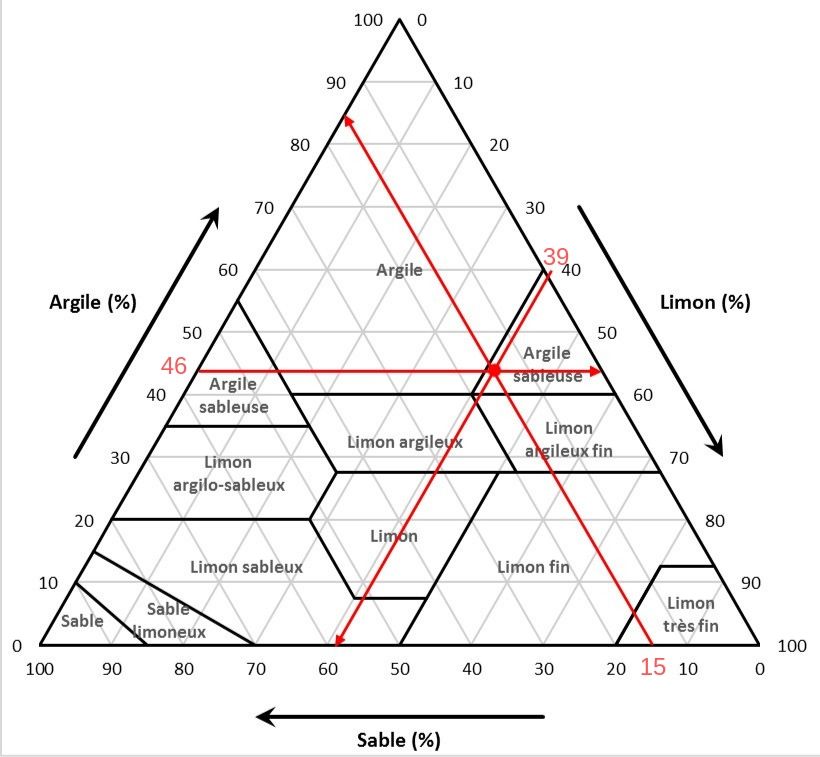

- Finally, to determine the texture of your soil, you will need to plot your results on the soil texture pyramid. This pyramid allows you to determine the exact classification of the soil you have tested. To do this, draw a line parallel to the axes of each layer (refer to the diagram). With these three lines drawn, you will find the point of intersection that will be in a box.

[caption id="attachment_67252" align="aligncenter" width="820"] Soil texture pyramid (you can find this blank pyramid on Wikipedia, others are also available online)

Soil texture pyramid (you can find this blank pyramid on Wikipedia, others are also available online)

Here we obtain a clayey-sandy soil.

Laboratory test

Sometimes, especially if you are new to a garden or planning to embark on a specific type of cultivation (such as a large vegetable garden), it may be wise to have a soil analysis conducted at an accredited soil laboratory. The report provided will indicate not only the soil composition: its richness, the levels of any pollutants (biocides, heavy metals, etc.), pH, and any advice to address various issues.

Please note: soils, even in our small garden plots, are rarely homogeneous. You will likely need to take several samples from different locations and average them.

Observe the spontaneous flora.

Wild Organic Indicator Plants

Observing the native plants in your garden, those once referred to as “weeds,” can provide you with insights regarding the composition of your soil.

- Sandy soil: couch grass, sea buckthorn, aster, wild lettuce, linaria…

- Loamy soil: couch grass, goosefoot… but there are few or no plants that are specific to this type of soil.

- Clayey soil: dandelion, bindweed, vetch, daisy, sorrel, creeping buttercup…

- Humus-bearing soil: fern, dead-nettle, nettle, sedge, ground elder…

Some organic indicator plants: Couch grass, dandelion, and nettle

Some organic indicator plants: Couch grass, dandelion, and nettle

Note: organic indicator plants provide only a general indication. Indeed, native plants, especially those we simply call “weeds,” often have a high ecological valence that allows them to colonise other types of soil, even if it is not their preferred habitat. Furthermore, as mentioned earlier, soil rarely contains just one component. In addition to soil texture, you can consider structure, moisture, nutrient levels, potential acidity, … In short, nothing beats a proper laboratory analysis.

Seek Advice from Your Neighbours

It may seem silly, but if your neighbours have been there longer than you, they likely know their land very well. Especially if they are farmers. Their land is their livelihood, and they often know the results of their soil analyses inside out.

- Subscribe!

- Contents

Comments